South Carolina's Natural Wildflower Communities —

THE MARITIME STRAND:

The maritime communities

Coastal beaches

Along the South Carolina coast, beaches form where ocean currents and waves deposit sand that was picked up by the waters from offshore coastal sites or brought down the rivers from inland areas. No vascular plants grow along the beach below the high-tide line because it is a dynamic zone, constantly changing because of the action of the wind and tides. Above the high-tide zone, a zone of detritus (driftline) develops, which is deposited by the tides. The dominant component of the detritus is the remains of smooth cordgrass from the nearby salt marshes, which washed down the tidal creeks. Seeds of two hardy species, sea rocket (Cakile harperi) and Carolina saltwort (Salsola caroliniana), are generally the first species to become established in this harsh environment. A rare beach plant is the federally endangered seabeach amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus), which occurs from upper Charleston County to North Carolina.

Coastal dunes

Landward from the driftline is the berm, a zone of fairly level, loose sand that is subject to heavy salt spray and is located above all but the highest spring tides. The coastal dunes form here. Dunes are mounds of unconsolidated sand formed in the berm area by winds blowing across the beach. Whenever a plant (or object) reduces the force of the wind, wind-borne sand is deposited and ultimately forms a dune. The plant most associated with building coastal dunes in the southeast is sea oats (Uniola paniculata). Young seedlings act as windbreaks, slowing the wind. As the wind slows, the sand it carries accumulates behind and against the leaves. As the sand is added, the plant grows, keeping its leaves above the rising sand. In a few years a dune builds many feet high.

Coastal dunes front the barrier beaches and barrier islands of the Carolina coast. They are interrupted where inlets and sounds allow the ocean to surge through, with the ocean's energy being dissipated inward to the tidal flats and marshes. Dunes are also the first line of defense against oceanic forces, especially hurricanes and winter storms. Just as winds can build dunes, they can destroy what they have created. Where the vegetation is killed, the wind erodes dunes. Preservation-minded coastal residents have long fought to protect dunes from excess disturbance, such as trails made by people or dune buggies. The South Carolina law against disturbing sea oats on public property has done much to protect coastal dunes.

Other grasses that help build the dunes are seaside panicum (Panicum amarum) and dune sandbur Cenchrus tribuloides). Once the dunes become fairly stable, various forbs become established to help further stabilize the dunes, including beach pea, horseweed, beach evening-primrose, dunes evening-primrose, camphorweed, seaside pennywort, and two species of cactus, prickly-pear (Opuntia compressa) and dune devil-joint (0. pusilla).

Swales develop between the dunes. These are low-lying areas that are protected from the salt-laden winds and where a fresh to brackish system may develop because rainwater collects and floats atop the heavier salt water. In this microhabitat, common marsh-pink (Sabatia stellaris) is abundant.

The dune communities may be replaced by maritime shrub thickets on barrier islands or on barrier beaches where accretion is occurring and the dunes are building seaward, which protects the inner dunes from the salt- laden winds, or where the shoreline has been stabilized for years. Maritime forests may in turn replace the maritime shrub thickets.

Maritime forests

Maritime forests occupy the barrier islands and barrier shores of the coast. The characteristic species are a variety of salt-tolerant, evergreen trees and shrubs. There is little herbaceous plant cover except in exposed sites, due to natural breaks in the canopy, and in disturbed areas.

On the ocean side, maritime forests are shaped (literally) by the effects of salt spray. The wind blowing from the sea carries salt, depositing it on the windward branches and leaves. These leaves and branches die from the salt, while those on the leeward side, protected from the salt spray, continue growing. The result is a “shearing effect” of the trees and shrubs. Inland, away from the effects of salt spray, the trees assume a typical appearance.

The characteristic evergreen trees of maritime forests are

live oak,

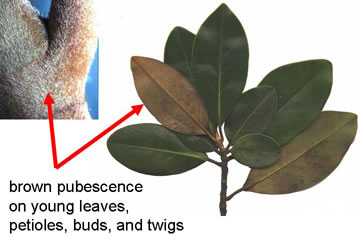

bull bay,

loblolly pine,

and laurel oak.

The subcanopy includes the evergreen trees

cabbage palmetto (Sabal palmetto).

American holly,

red bay (Persea borbonia),

Hercules'-club (Zanthoxylum clava-herculis),

and in more open sites,

wax myrtle,

yaupon (Ilex vomitoria),

wild olive,

and southern red cedar (Juniperus silicicola).

Herbaceous wildflowers are sparse because of the dense canopy, but two species can be found in more open sites, prickly-pear cactus and trailing bluet (Houstonia procumbens).

The maritime forests along the Atlantic Coast have been extensively timbered since colonial times. No original growth stands exist along the South Carolina coast, with the possible exception of the interior of St. Phillips Island in Beaufort County where low swales prevented timbering. Islands such as Capers Island in Charleston County and Daufuskie Island in Beaufort County have had extensive agricultural fields in the interior, and the present forests are secondary growth.

Timbering began in the maritime forests in the 1700s, mainly for live oak to build wooden sailing vessels. After the War of 1812, “live oak mania” began.

Expeditions were sent from the northern shipyards to the Atlantic and Gulf coasts to harvest live oak. After the invention of iron and steel ships, live oak was given a reprieve. Timber companies then began to harvest the pines of the maritime forests. Maritime forests of the lowcountry today are secondary forests. The existing large live oaks are either ones that were left, for whatever reasons, or that came from seedlings. Live oak is a fast-growing tree on good sites and can reach an impressive size in 50 years. The large live oaks that line plantation avenues were planted starting in the 1700s (note their large size today).

Salt marshes

Salt marshes occur on regularly flooded, peaty substrates along tidal inlets and behind barrier islands and spits. This community is species- poor, often supporting pure stands of smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora); however, it is one of the most productive in the world. It is the dominant wetland in the coastal zone of South Carolina, comprising approximately 150,000 acres. As cordgrass dies, it is washed into the inlets and the ocean, where it forms the basis of the estuarine food chain.

Three forms of smooth cordgrass occur: tall, medium and short. The tall Spartina grows next to the tidal creeks in relatively deep water, where it receives an energy subsidy from the tidewater. Away from the creek the tall cordgrass grades into the medium. The medium then grades into the short. Short cordgrass occurs at the highest elevation where it is flooded daily, but only to a depth of a few inches to one foot.

In the short zone, two species that also occur in the adjacent salt shrub thickets intermix with the short Spartina: sea lavender (Limonium carolinianum) and saltmarsh aster (Aster tenuifolius), adding a touch of color to the otherwise drab salt marshes.

Salt flats

Salt flats are formed where tidal waters drain incompletely and the soil becomes very sally. As the water evaporates, it leaves behind the salt, which often forms a white crust on the soil. Even the most salt-tolerant species cannot survive in these hypersaline areas, and the center of flats is often barren. However, as salinity decreases toward the margins, a variety of fleshy halophytes, salt-loving grasses, and other herbs appear. Closest to the center are perennial glasswort (Salicornia virginica) and saltwort (Batis maritima), which are obligate halophytes that tolerate high salinity. Salt flats grade into either salt marshes or salt shrub thickets. Intermixed with saltwort and glasswort are diminutive forms of species associated with the salt marshes and salt shrub thickets: sea ox-eye, marsh-elder, smooth cordgrass, sea lavender, saltmarsh aster, and seaside goldenrod.

Maritime shell forests

Natural and Native American shell deposits are scattered along the coast in salt marshes and on the tips of landmasses within estuaries. The natural shell deposits are not unique floristically. They generally support species of the adjacent maritime communities. The Native American deposits, however, are floristically unique and have only recently been studied along the Carolina coast. The key environmental parameter determining the floristic composition of the Native American shell deposits is the presence of calcium from the shells. Several calcium-loving species, called calcicoles, occur and are mixed with species of the adjacent maritime forests and salt shrub thickets.

Native American shell deposits are of three types: shell rings, shell mounds, and shell hummocks, which occur on marsh islands or on the mainland.... The shell ring is a circular deposit of shells that rises several feet above the marsh. The shell mound is a mass of shells that is raised considerably higher than the shell ring (from 10 to 30 feet high). Shell hummocks are shells that were deposited in piles or in sinuous formations, probably as part of a campsite, on the mainland or on marsh islands. Considerable debate exists about the origin of these Native American shell deposits.

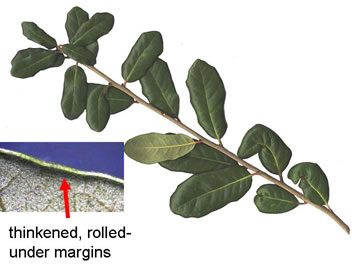

Shell rings are either isolated in the marsh or attached to a landmass. The isolated shell rings harbor few calcicoles, with only tough bumelia (Bumelia tenax) and shell-mound buckthorn (Sageretia minutiflora) being common. The shell rings attached to an adjacent landmass, however, harbor many of the rare calcicoles that are found on the high shell mounds and shell hummocks.

The shell mounds and shell hummocks harbor a maritime shell forest. This is a rare forest community along the coast and, at the date of the printing of [A Guide to the Wildflowers of South Carolina], has not been formally classified. There is no doubt, however, that the maritime shell forest is unique.

Maritime shell forests harbor a variety of woody trees, shrubs, and herbs that thrive in high-calcium soils. Trees and shrubs include

tough bumelia (Bumelia tenax),

basswood (Tilia heterophylla),

red buckeye (Aesculus pavia),

hackberry (Celtis laevigata),

Carolina buckthorn (Rhamnus caroliniana),

shell-mound buckthorn (Sageretia minutiflora),

rough-leaved dogwood (Cornus asperifolia),

the rare southern sugar maple (Acer barbatum)

and Godfrey’s forestiera (Forestiera godfreyi).

Rare herbs include

mottled trillium (Trillium maculatum),

Cynanchum scoparium,

Indian-midden morning-glory (Ipomoea macrorhiza),

and crested coral-root (Hexalectris spicata).

Sites with southern sugar maple are the most spectacular. In the fall, their leaves turn a distinctive red, and the community can be spotted from the air. Maritime shell forests share many species in common with the inland calcareous forests since both are influenced by calcium in the soil.

South Carolina's Natural Wildflower Communities is adapted from A Guide to the Wildflowers of South Carolina by Richard D. Porcher and Douglas A. Rayner. Used by permission.

To see pictures or additional information about a particular plant, click its name or its picture.