Joseph Lord, Natural Scientist

by Amy Hackney Blackwell*

Reprinted from Chinquapin, Fall 2014. Used by permission.

To see pictures or additional information about a particular plant, click its name.

Joseph Lord was not a scientist. By trade he was a minister. He graduated from Harvard in 1691 and spent four years studying theology and teaching in Dorchester, Massachusetts. In 1695 he and a group of parishioners went to South Carolina to found a new town: Dorchester, on the Ashley River 15 miles inland from Charleston (Anon, 1920). There he became a plantation owner, the father of a large family – and a natural historian.

Around 1700, Lord got involved with James Petiver, an apothecary in London who maintained a stable of collectors who eagerly sent him specimens of plants and animals from newly discovered lands. Petiver advertised on ships sailing away from England, soliciting contributions to his collections in return for glory for the collector (Bellis, 2009). Some of his contributors never met him. Lord certainly never went to London. Nevertheless, Petiver seems to have had quite a virtual presence in Charleston; John Lawson heard of him through Robert Ellis and Edmund Bohun, Charleston residents who themselves sent specimens to Petiver. Lord’s neighbor Daniel Henchman also collected for Petiver, reportedly traveling more than 300 miles into the country, but he died in 1709 and none of his specimens survive (Dandy, 1958).

Lord’s specimens did survive, or at least some of them did. Petiver took Lord’s herbaria, along with those of Lawson, Ellis, and many others, and bound them in volumes that ended up in Sir Hans Sloane’s collection after Petiver died in 1718. Today the Sloane Herbarium of the Natural History Museum London holds about 125 specimens collected by Lord between 1704 and 1707. My colleagues Patrick McMillan and Christopher Blackwell and I have digitally photographed these specimens, which are posted on our Botanica Caroliniana website. We published an article including determinations of taxa in Phytoneuron last summer.

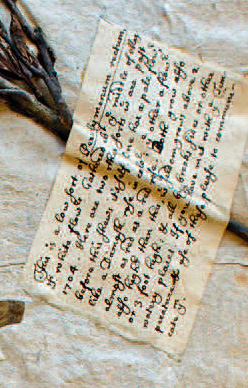

Lord sent Petiver meticulous notes along with his plant specimens – describing habitat, habit, taste, medicinal uses, supposed taxonomy, bloom dates and collection dates. Lord’s handwriting is tiny, beautiful, and easy to read.

Two things make Lord’s specimens particularly noteworthy. First, they were collected very early in the period of European colonization of the Carolinas, well before the region was thoroughly transformed by agriculture and introduced plants. Second, Lord sent Petiver meticulous notes along with his plant specimens – describing habitat, habit, taste, medicinal uses, supposed taxonomy, bloom dates and collection dates. Lord’s handwriting is tiny, beautiful, and easy to read.

Lord’s notes together with his surviving letters reveal a natural scientist – by which I mean a person naturally inclined to observe details of the world around him and to ask how those details fit with others. He didn’t have many resources – his only references were a borrowed copy of John Gerard’s 1597 Herbal and the slightly more up-do-date Culpepper’s English Physician, published in 1652 – and had no way of getting more books. His letters and notes to Petiver constantly plead for more information, and if possible some books sent from London (Lord, 1920).

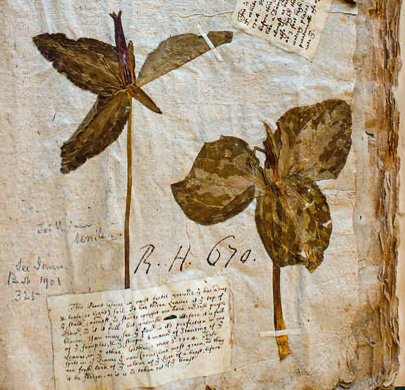

Trillium maculatum

But that didn’t stop Lord from jumping into this science project with both feet. He tried to send Petiver as much information about his world as he could, through the medium of dried plants, bits of shell, and other oddments. He had a talent for description. For instance, he wrote of a Trillium maculatum Raf. (H.S. 284 f. 4) that “This plant grows in moist fertile ground that has a deep loose (or light) soil. It has three leaves at the top of the stalk, amidst which stands upright one dark reddish purple flower, when it is full; but greenish before it is full blown. You may see the flower in its perfection in one of the samples, & the shape & manner of standing of the leaves, in the other. Gathered May 3d, 1704. Those spots in the leaves that now (dried) look most green, when they are fresh look of the color of the liver of a beast…, as it is when taken out of the beast.”

Wow! The color of the liver in a freshly killed beast? That’s evocative!

Lord’s notes are full of such details. He describes Ilex ambigua (Michx.) Torrey (H.S. 285 f. 8) as having leaves that smell like potatoes beginning to rot, and notes that an Indian recommended it as a treatment for “the Head-ack in such as have Agues.” He observes that Lobelia nuttallii Schultes (H.S. 284 f. 42) “chiefly seems to delight in ground that is somewhat moist, & grows only among Grass & weeds.” Ctenium aromaticum (Walter) Wood (H.S. 268 f. 1) has a root that “tastes somewhat like Pellitory of Spain, but I think a little more subtile, hot, & Pierceing.”

Of Crotalaria rotundifolia Walter ex J.F. Gmelin (H.S. 284 f. 75) he writes: “This plant spreads on the ground, only it has a stalk rising from among the leaves which bears divers yellow blossoms after which succeed short cods, when they are ripe black with a blewish dust on them, which have seed in them that rattle. Gathered in the beginning of June, or end of May, 1704. Are in seed now, Jun. 15.”

And so on. The majority of Lord’s specimens contain observations like these. He refers back to specimens sent in previous shipments, expecting Petiver to remember them. He reports on the behavior of particular taxa over the years. He passes on bits of wisdom he has heard from Indians or local children.

Lord’s specimens are organized taxonomically. Although he laments his inability to identify and classify species, and his work predates Linnaeus by half a century, his specimens are laid out in an order that fairly accurately corresponds to modern families. So despite an almost complete lack of training or scientific references, Lord and Petiver were participating in the groundwork that led to modern plant taxonomy.

...he made his collections for the purest of reasons – fascination with his subject and a desire to both learn more and to share what he knew.

Joseph Lord was a voice in the wilderness. As far as I can tell, he made his collections for the purest of reasons – fascination with his subject and a desire to both learn more and to share what he knew. He wasn’t aiming at publishing a book or joining the Royal Society, like Mark Catesby, or drumming up colonists, like John Lawson. He had an identity – he was a minister and the founder of a colony. He also happened to form an interest in the natural history of his new home, and seized on a way to connect it to the larger world of scientific inquiry.

Qualified or not, he did his best with what he had. Working with a medieval herbal and whatever he had learned in 1690s divinity school, with virtually no mail and certainly no Internet, Lord turned himself into a naturalist. And between him and Petiver, he produced a collection that could in fact make a real contribution to the development of scientific knowledge, a contribution that has even more value today. We can’t go out in the field to survey the plants that were growing in 1700. But thanks to people like Lord, amateurs with the guts to submit their work to the larger scientific community, we have data we could never collect ourselves. Lord’s misgivings notwithstanding, he did a great job. He ought to be proud.

To read more about Lord and the collection of his specimens housed at the Sloane Herbarium of the Natural History Museum in London, download Collected in South Carolina 1704-1707: the Plants of Joseph Lord.

References:

- Anon. 1920. Early Letters from South Carolina upon Natural History. The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 21: 3–9.

- Bellis, V. 2009. John Lawson’s Plant Collections from North Carolina 1710-1711. Castanea, 74(4):376-389.

- Dandy, J.E. (ed.). 1958. The Sloane Herbarium. Trustees of the British Museum, London.

- Lord, J. 1920. Letter from Joseph Lord. The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 21: 50–51.

* Amy Hackney Blackwell has a Ph.D. in plant science from Clemson University. She works for the legal education website Quimbee.com.