Ferns: Explanation of Terms

adapted from How to Know the Ferns by Frances Theodora Parsons, illustrated by Marion Satterlee and Alice Josephine Smith. Originally published in 1899 and now in the public domain.

To see photographic examples of a term, click the camera next to it in the list of botanical terms.

A fern is a flowerless plant growing from a rootstock with leaves or fronds usually raised on a stalk, rolled up in the bud,* and bearing on their lower surfaces the spores, by means of which the plant reproduces.

Rootstock

A rootstock is an underground, rooting stem. Ferns are propagated by the growth and budding of the rootstock as well as by the ordinary method of reproduction.

The fronds spring from the rootstock in the manner peculiar to species to which they belong —

The Osmundas, the Evergreen Wood Fern, and others grow in a crown or circle, the younger fronds always inside.

The Mountain Spleenwort is one of a class which has irregularly clustered fronds.

The fronds of the Brake are more or less solitary, rising from distinct and somewhat distant portions of the rootstock.

The Botrychiums usually give birth to a single frond each season, the base of the stalk containing the bud for the succeeding year.

* Ophioglossum and the Botrychiums, not being true ferns, are exceptions.

Fronds

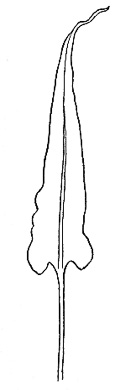

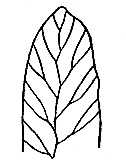

SIMPLE

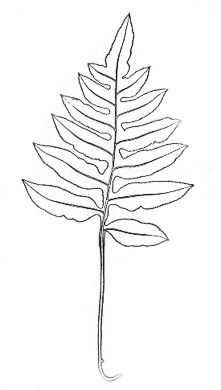

PINNATIFID

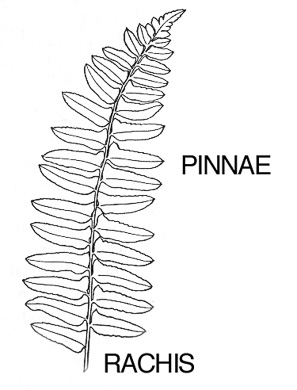

ONCE-PINNATE

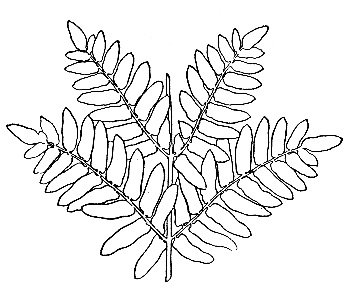

TWICE-PINNATE

A frond is simple when it consists of an undivided leaf such as that of the Hart's Tongue or of the Walking Leaf.

A frond is pinnatifid when cut so as to form lobes extending halfway or more to the midvein. A frond is once-pinnate when the incisions extend to the midvein. Under these conditions the midvein is called the rachis, and the divisions are called the pinnae.

A frond is twice-pinnate when the pinnae are cut into divisions which extend to their midveins. These divisions of the pinnae are called pinnules.

A frond that is only once-pinnate may seem at first glance twice-pinnate, as its pinnae may be so deeply lobed or pinnatifid as to require a close examination to convince us that the lobes come short of the midvein of the pinnae. In a popular handbook it is not thought necessary to explain further modifications.

The veins of a fern are free when, branching from the midvein, they do not unite with other veins.

Spores

Ferns produce spores instead of seeds.

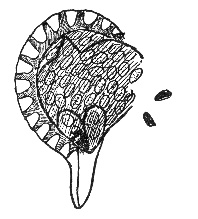

These spores are collected in spore-cases or sporangia. Usually the sporangia are clustered in dots or lines on the back of a frond or along its margins.

These patches of sporangia are called sori or fruit-dots. They take various shapes in the different species. They may be round or linear or oblong or kidney-shaped or curved.

At times they are naked, but more frequently they are covered by a minute outgrowth of the frond or by its reflexed margin. This covering is called the indusium. In systematic botanies the indusia play an important part in determining genera. But as often they are so minute as to be almost in visible to the naked eye, and, as frequently they wither away early in the season, I place little dependence upon them as a means of popular identification.

Fertile fronds & sterile fronds

A fertile frond is one which bears spores.

A sterile frond is one without spores.

Before attempting to identify the ferns

Before attempting to identify the ferns… it would be well to [read] the Explanation of Terms, and with as many species as you can conveniently collect, on the table before you, to master the few necessary technical terms, that you may be able to distinguish a frond that is pinnatifid from one that is pinnate, a pinna from a pinnule, a fertile from a sterile frond.

You should bear in mind that in some species the fertile fronds are so unleaf-like in appearance that to the uninitiated they do not suggest fronds at all. The fertile fronds of the Onocleas, for example, are so contracted as to conceal any resemblance to the sterile ones. They appear to be mere clusters of fruit. The fertile fronds of the Cinnamon Fern are equally unleaf-like, as are the fertile portions of the other Osmundas and of several other species.

In your rambles through the fields and woods your eyes will soon learn to detect hitherto unnoticed species. In gathering specimens you will take heed to break off the fern as near to the ground as possible, and you will not be satisfied till you have secured both a fertile and a sterile frond. In carrying them home you will remember the necessity of keeping together the fronds which belong to the same plant….